Have you ever struggled to remember the lecture you’ve just listened to while effortlessly recalling a catchy song from your childhood? Ever wonder why is it so? The information processing theory offers a glimpse into these processes. By delving into it, you can grasp how our brains tackle information and apply these insights to maximize your cognitive potential.

In this article, our custom essay writing team will unpack information processing theory in a way that can benefit your studies. You’ll learn how it can empower you to study more efficiently, retain knowledge longer, and boost academic performance.

🔤 What Is Information Processing Theory?

Information processing theory (IPT) reveals how our brains take in information and store it as memories. It assumes that our memory works in stages. First, we perceive something through sensory memory. The brain filters this input and sends the part to which we pay attention to our short-term memory. Finally, we store information permanently in our long-term memory.

All these stages remind us of how computer memory works. That’s no accident: one of the central assumptions of IPT is that our brain operates like a computing machine.

📜 History of Information Processing Theory

IPT has a rich and exciting history, dating back to the 1950s. Since its inception, it has expanded significantly and remains vital for understanding how we perceive, interpret, and utilize information.

When Was the Information Processing Theory Developed?

This framework emerged in the 1950s and 1960s, with its origin closely linked to the advent of high-speed computers. Researchers spotted noteworthy parallels between how computers tackle information and how individuals engage in comparable cognitive operations.

This inspired a whole new way of thinking among psychologists. Before then, psychology concentrated solely on observable behaviors, ignoring what was occurring inside our heads. IPT shifted this mindset, highlighting the pivotal role of our internal mental mechanisms.

Who Developed the Information Processing Theory?

This theory cannot be attributed to a single scholar. It came out through the collaboration of multiple psychology scientists. One outstanding figure was George A. Miller, who recognized the parallels between people’s cognitive functioning and computer operations.

Let’s explore the contributions of some notable figures, including George A. Miller.

George A. Miller: Short-Term Memory

George Armitage Miller pioneered IPT with his groundbreaking article “The Magical Number Seven, Plus or Minus Two.” Here, he introduced “chunking” as a fundamental aspect of memory and learning. Miller contended that our minds have a limited capacity for processing information. He suggested that the maximum number of meaningful items we can effectively “chunk” or group together is 5-9.

Think of memorizing a phone number. In many places, it consists of ten digits. According to Miller, we don’t remember each digit separately. Instead, our minds naturally organize the numbers into chunks, like this: 123-456-7890.

Atkinson & Shiffrin: Three Stages of Memory

In 1968, building upon Miller’s work, psychologists Richard Atkinson and Richard Shiffrin formulated a multi-store memory model. Often called the Atkinson-Shiffrin model, it views the human memory as a three-step process:

- Sensory memory stores information we get through our senses for a moment.

- Short-term memory briefly holds information on which we’re currently focused.

- Long-term memory keeps information for a long time if we rehearse it or actively engage with it.

Baddeley & Hitch: Working Memory Model

Atkinson and Shiffrin’s model had its flaws. It depicted short-term memory as a passive storage “slot.” Psychologists Alan Baddeley and Graham Hitch disagreed with this view and suggested something better: working memory. Think of it as a dynamic workspace where information is temporarily held and actively manipulated, organized, and utilized in cognitive tasks.

Baddeley and Hitch’s model introduced four elements of working memory:

- The central executive is like the boss of your memory. It directs other parts of working memory. For instance, when solving a math problem, the central executive helps you focus and decide which information to heed.

- The phonological loop is like a little voice in your head that allows you to remember sounds and words. Ever repeat a phone number to yourself to memorize it? That’s your phonological loop at play.

- The visuospatial sketchpad is where you hold and handle visual information. When you try to remember the layout of a new place, you are using this component.

- The episodic buffer serves as a short-term storage space where different types of information are combined. It enables you to recall a certain episode from your past by bringing together various details about that incident.

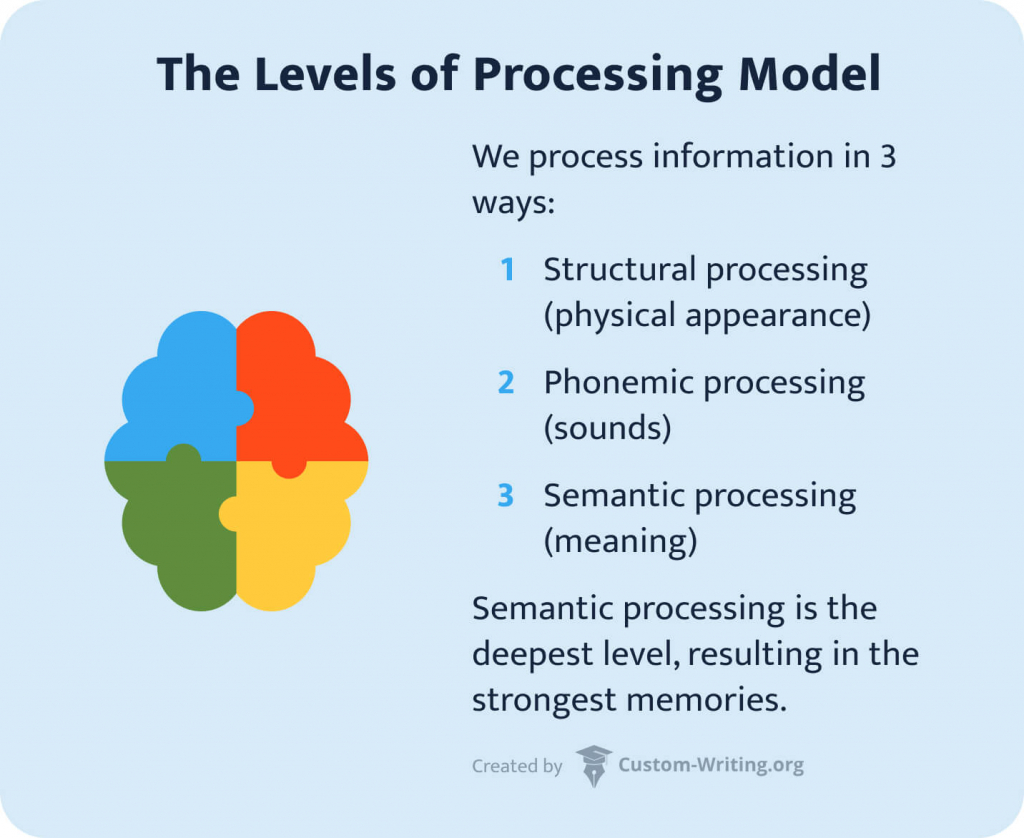

Craik & Lockhart: Levels of Processing

Craik and Lockhart also challenged the Atkinson & Shiffrin model. They disagreed that repeating things again and again was the most effective way to remember them. Instead, they assumed that how deeply you think about something is what counts. This is what their levels of processing model is about.

Craik and Lockhart identified three levels of processing:

- Structural processing is when you pay attention to the physical attributes of something, like color, size, and shape. It doesn’t require deep thought and leads only to short-term retention of data.

- Phonemic processing means encoding sounds. It results in slightly better recall but is still considered shallow processing.

- Semantic processing is when you reflect on the meaning of something and relate it to other information you know, your everyday life, the task at hand, etc. It is the best way to create solid, long-lasting memories.

Rumelhart, Hinton, & McClelland: Parallel-Distributed Processing

Ultimately, Rumelhart, Hinton, and McClelland further advanced the theory with their parallel-distributed processing (PDP) model. It represents the brain as a network of multiple processing units working together.

Imagine a person driving. While steering the vehicle, the driver simultaneously pays attention to the surroundings, like other cars, traffic signs, and pedestrians. The brain’s ability to tackle several things at once is called “parallel processing.”

The PDP model also clarifies how our memories are saved. They are not kept in a single brain region but distributed across a myriad of brain cells (neurons). When we recollect things, many different neurons collaborate to retrieve those memories.

📝 Information Processing Theory: Summary of Cognitive Processes

We’ve just introduced you to a bunch of models within IPT. Now, let’s briefly examine the key cognitive processes it deals with. It will help you realize what you should work on to advance your learning.

Memory

Memory is in the limelight of IPT. This cognitive process occurs in stages, starting with encoding. Information we obtain from the outside is encoded into our brains and stored in three stages: sensory, short-term, and long-term memory. However, we don’t memorize something for its own sake. So, the last stage of memory is retrieval — recalling information.

Attention

Attention is like a mental spotlight that lets us focus on particular things. For instance, when you’re watching TV, and someone asks you a question — you have to pay attention to hear and understand before you can answer.

Attention and memory are closely intertwined. Selective attention is indispensable for information to move from our quick, brief sensory memory into our short-term memory.

Metacognition

Metacognition means reflecting on your own thinking. It’s the awareness of how you learn and remember information. This concept is significant to IPT since it allows us to take advantage of our knowledge of how our brains work. For instance, you can enhance your memory by applying various metacognitive tools, such as mnemonics or reflection.

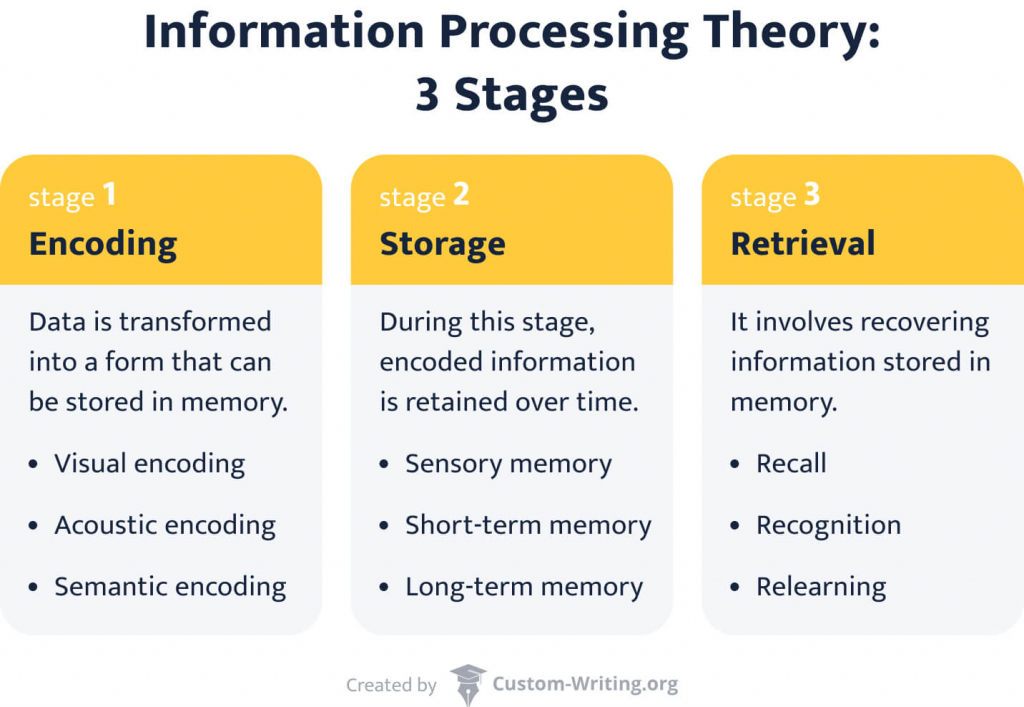

👣 Information Processing Theory: Stages

Now, let’s discuss each phase of IPT in detail! Learning this will help you understand how to make something stick to your memory.

1. Encoding

Encoding means transforming data into a form your brain can store. This process is crucial for creating memories and enabling you to access the information later.

There are three types of encoding:

- Visual encoding. It deals with images. Imagine yourself reading the word “apple.” In this case, your brain encodes the letters’ visual characteristics and the word’s shape.

- Acoustic encoding. It tackles sounds. Consider this: if you hear the word “apple,” your brain encodes the sound it produces.

- Semantic encoding. It processes the meanings. Your brain would use this type if you thought about what the word “apple” represents and linked it to related concepts (like fruit or taste).

Encoding information can occur both automatically and effortfully. Automatic processing refers to the effortless, almost involuntary encoding of information. For instance, after you become skilled at typing on a keyboard, you can do it mechanically—your fingers seem to know where to go.

Meanwhile, effortful processing is conscious, demanding mental effort and active attention. Studying for an exam or grasping complex math concepts demands effortful processing.

2. Storage

Storage is the stage during which encoded information is retained for subsequent use. It is akin to saving files on a computer. Once our brains have processed and understood something, they create mental “file folders” and hold the data there.

Storage occurs at three levels of memory: sensory, short-term, and long-term. Let’s consider them in detail!

Stage 1: Sensory Memory

Sensory memory is where the senses (sight, sound, touch, taste, and smell) take in information and briefly hold onto it. It’s like a quick shot of our surroundings. Imagine looking at a painting — your sensory memory briefly holds that image even after you’ve turned away. Sensory memory can keep a maximum of 4 items and lasts 0.5-3 seconds.

Forgetting in sensory memory occurs due to decay. In other words, information kept in this temporary storage just fades away quickly if we don’t pay attention.

Stage 2: Short-Term Memory

Short-term memory is like a transitory storage for information we actively use. Remembering a phone number as you dial it is an illustration of short-term memory at work. This storage helps us bear things in mind for a while, usually around 15-30 seconds. It can contain 5-9 chunks of information at a time.

Why do we forget information stored in short-term memory? There are several reasons:

- Decay — information fades away if we don’t rehearse it.

- Interference — when new sensory information competes with the old, it is harder to retrieve the earlier memory.

- Distractions, stress, fatigue, and aging.

Stage 3: Long-Term Memory

Long-term memory stores information for minutes or even years. Your childhood home address or your favorite song lyrics are examples of memories kept here.

Sometimes, we forget things we long remembered. Why does it happen? At some times, other memories can get in the way. At other times, no cues are present to awaken our hidden memories. Stress, distraction, aging, brain injury, or neurological disorders can also make it hard to recollect something.

3. Retrieval

Retrieval means bringing stored data from long-term memory back into consciousness.

The brain accesses the encoded information and drags it back into the spotlight. Cues or associations can trigger this process.

There are three ways we retrieve information:

- Recall. Pulling a memory out without any cues or hints is known as recall. It’s like remembering a friend’s phone number without looking it up.

- Recognition. This one is easier – it’s like noticing a familiar face in a crowd. It means recognizing information we’ve encountered before.

- Relearning. It entails learning things you’ve forgotten. An example is relearning how to play a guitar after not playing it from a young age.

👨🎓 Example of Information Processing Theory in Practice

Imagine Sam, a student who recently started learning French. Using Sam’s journey of learning a foreign language, we’ll discuss how IPT works in practice.

1️⃣ Encoding:

Before information can proceed to Sam’s memory, it should be encoded. So, Sam’s first step is to receive information through his senses. He reads the stories in his textbook to see what French words look like and listens to the teacher to hear how they sound.

2️⃣ Sensory memory:

Once Sam encounters unfamiliar French phrases, his sensory memory briefly holds their visual layout and pronunciation before further processing.

3️⃣ Attention:

To memorize these new words, Sam has to focus. This is necessary for the information to be moved to short-term memory. Otherwise, it will be quickly forgotten.

4️⃣ Short-term memory:

Some of the new French vocabulary and grammar rules that Sam is focusing on are transferred to his short-term memory. However, without rehearsal or repetition, this knowledge can get lost through forgetting.

5️⃣ Rehearsal for long-term storage:

Sam practices the new vocabulary repeatedly. It helps strengthen the neural pathways in his brain and facilitates durable retention.

6️⃣ Long-term memory:

Sam’s long-term memory stores French vocabulary, grammar rules, and cultural nuances. Days or years will pass, but Sam will still bear these details in mind. He can also apply this knowledge in new contexts, like comprehending French texts and engaging in conversations.

7️⃣ Retrieval:

Whenever Sam uses his French knowledge, he recovers it from his long-term memory. For instance, he can recollect the French vocabulary when composing an essay in this language.

8️⃣ Metacognition:

Throughout the learning process, Sam practices metacognition — thinking about his studies. He monitors his comprehension, evaluates his progress, and adjusts his studying habits.

Understanding how he learns will allow Sam to optimize his studies and enhance his ability to acquire new language skills.

⚖️ Information Processing Theory: Strengths and Weaknesses

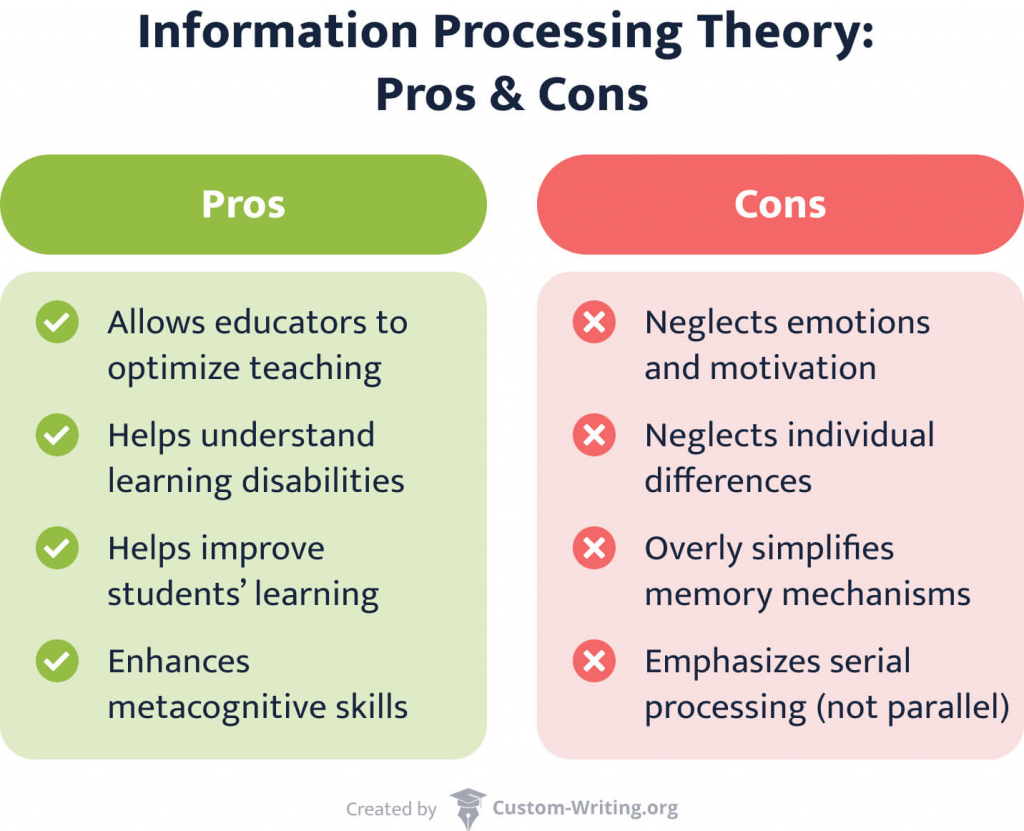

IPT offers valuable insights into cognitive processes, but it also has certain limitations. Further, we’ll discuss this theory’s main pros and cons for teaching and learning.

Why Is Information Processing Theory Important?

IPT offers several benefits to teachers and learners:

- Guidance for curriculum adaptation. Teachers can optimize students’ learning by incorporating memory-enhancing techniques like mnemonics and multimodal instruction into their practice.

- Understanding learning disabilities. IPT aids in recognizing and understanding the cognitive processes involved in learning. Thanks to that, educators and psychologists can identify students’ learning challenges early on and devise timely and targeted interventions.

- Improved study efficiency. Students can apply information processing principles to enhance their study habits. For instance, they can incorporate active recall, spaced repetition, and mnemonics into their learning routine.

- Enhancement of metacognitive skills. The theory promotes metacognition, enabling students to monitor and regulate their learning. This leads to increased self-awareness, self-regulation, and strategic thinking, which are vital for academic success.

Limitations of Information Processing Theory

Criticism of information processing theory is mainly linked to its reliance on computer-based metaphors to explain human cognition. Some argue that this approach oversimplifies the human mind’s complexity.

Some other critical points against the theory include:

- Neglect of emotions and motivation. The theory overlooks their impact on learning, memory, and information processing.

- Limited consideration of individual differences. Critics argue that the theory’s emphasis on generic information-processing stages does not adequately account for individual learning differences.

- Inadequate representation of memory mechanisms. Some scholars suggest that while the theory is informative, it does not encompass the full spectrum of memory processes. For instance, it says nothing about autobiographical, emotional, and implicit memory.

🎓 How to Use the Information Processing Theory for Enhanced Learning

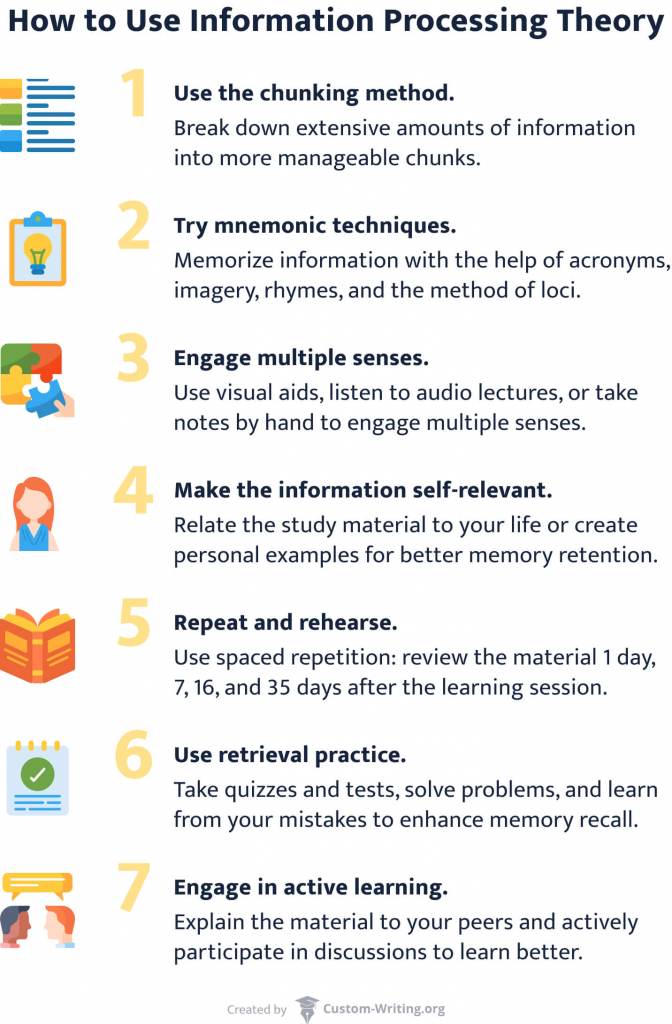

Now, you might wonder how to apply information processing theory in the classroom and for self-studying. We’ve gathered some valuable practical tips from cognitive psychologists and educational experts. Check them out!

Use the Chunking Method

Chunking involves breaking down extensive amounts of information into more manageable chunks. When you deal with smaller amounts of data, you will remember them more willingly and easily.

For instance, if you’re studying a history chapter, you can chunk the material based on different periods or milestone events. Diagrams, flowcharts, and mind maps can be beneficial for representing grouped chunks visually.

Try Mnemonic Techniques

Mnemonic techniques involve organizing information so as to make it easier to remember. Here are some of them you can try:

- Acronyms. Create a word or phrase where each letter represents the first letter of a list of concepts. An example is the acronym HOMES, which helps remember the names of the Great Lakes.

- Imagery. Associate the information with vivid mental images to make recalling it effortless.

- Rhymes and alliteration. If you’re a poetry fan, try making rhymes or alliterations to make information more memorable.

- Method of loci. Mentally place things you want to remember in a familiar space, like your bedroom. Then, visualize yourself walking through that location to recall them.

To get the most benefits from using these techniques, create mnemonic devices that are personally meaningful or creative. However, using ready-made mnemonics is also helpful.

Engage Multiple Senses

Engaging multiple senses while studying is an effective way to enhance learning and memory retention. It can lead to stronger neural connections and a deeper understanding of the material. Below, you’ll find tips on engaging multiple senses while learning.

👁️ Visual learning:

- Use diagrams, charts, and graphs to aid visual memory.

- Create or find colorful and visually stimulating study materials.

- Watch educational videos or animations.

👂 Auditory learning:

- Record yourself reciting essential information and play it back.

- Listen to educational podcasts, lectures, or audio recordings.

- Explain concepts out loud to yourself or discuss them with a study partner.

️🖐️ Kinesthetic learning:

- Use physical objects or models (like props for a history lesson) to understand abstract concepts.

- Write and rewrite essential information to reinforce muscle memory.

- Use tactile materials such as textured study aids or stress-relief objects to keep your hands engaged while studying.

Make the Information Self-Relevant

Making information self-relevant is a powerful strategy for enhancing learning. Here are some methods you can try:

- Relate the material to your life. Try to link the material to your experiences, ambitions, or interests. For instance, when learning a new language, you can use the learned vocabulary to describe your daily routines.

- Identify the value and importance. Reflect on why the information is significant to you. Understanding the practical applications of the material will make it more meaningful and memorable.

- Create personal examples. Make up your own examples that demonstrate the concepts you are studying.

- Teach others. Discuss the material with peers and try to teach them what you’ve learned. It will help you practice recall and understand the information more deeply.

Repeat and Rehearse

We often forget a significant portion of what we learn rather quickly. There’s even a concept known as the “forgetting curve.” It explains how our memory of newly learned information decreases over time if we don’t actively try to remember it. For instance, within 24 hours, students who do not repeat the material tend to forget around 70% of what they heard during the lecture.

To review information regularly, you can try spaced repetition. It involves reviewing material at specific intervals:

- the day after the initial study session;

- 7 days after;

- 16 days after;

- 35 days after the study session.

Consider using popular spaced repetition apps like Anki and Memorang. They employ sophisticated spaced repetition algorithms that automatically schedule review sessions based on the timing of previous reviews and the user’s performance.

Use Retrieval Practice

Retrieval practice is a highly effective learning technique. It involves actively recalling information rather than passively re-reading or re-studying material. Here are some practical tips on how to use it:

- Quiz yourself. Take practice tests or quizzes related to the material you are studying. Many textbooks and online resources offer practice questions for this purpose.

- Practice problem-solving. Subjects like math, science, or engineering will offer you plenty of opportunities to try this technique. Work through practice problems without peeking at the solutions until you have given it your best effort. This will reinforce your problem-solving skills and enhance your memory of key concepts.

- Learn from mistakes. While engaging in retrieval practice, note the questions or topics you struggle with. Reflect on why you found them challenging. Use these insights to guide your further study and practice sessions.

Engage in Active Learning

Active learning entails your engaged participation in study activities, not merely passive reading or listening. Check out some of the most helpful active learning strategies:

- Peer teaching. Collaborate with classmates to explain concepts to each other. This method can involve forming study groups, teaching a specific topic to a peer, or participating in peer-led discussions.

- Concept mapping. Consider visually presenting the relationships between various concepts. You can use paper and colored pencils or opt for online tools.

- Interactive lectures. Don’t be afraid to actively participate in class discussions, ask questions, and engage with the material during lessons. Take comprehensive notes and seek clarification on any points that are confusing to you.

- Debates and discussions. Participate in debates or structured discussions on controversial topics related to your course. This practice enhances critical thinking skills and exposes you to diverse perspectives.

🧠 Bonus Tips to Improve Your Information Processing

We’ve prepared some bonus tips to help you hone your information-processing skills and boost your productivity.

- Cultivate your conceptual thinking. Instead of simply memorizing isolated facts, focus on comprehending the underlying concepts and their interconnections. This broader view will foster your understanding.

- Connect old and new. Relate newly acquired information to familiar concepts, draw parallels, and look for patterns or similarities. This method aids in memory retention and underscores the relevance of the new material.

- Prioritize quality sleep. Ensure you get adequate restorative sleep to maintain optimal cognitive function and memory consolidation. Establish a relaxing night routine and aim for 7-9 hours of sleep per night.

- Paraphrase what you learn. Rephrasing the material reinforces your understanding and retention. Try explaining concepts without looking at your notes. Use diverse examples or analogies to convey the same idea.

- Teach others. Share what you’ve mastered with peers, friends, or family. Teaching others reinforces your understanding and allows you to gain new insights through discussions and feedback.

- Take regular breaks. Practice the Pomodoro technique or similar time management strategies to incorporate regular breaks into your study routine. Short breaks can increase focus and productivity and prevent mental fatigue.

- Stay organized. Carefully arrange your study materials to make information easily accessible. Use planners, digital calendars, and note-taking apps to keep track of your study schedule and tasks.

- Minimize distractions. Find a quiet and comfortable study place where nothing will interrupt you. This will make it easier for you to stay concentrated.

- Vary your study methods. Try flashcards, diagrams, or practice quizzes to see what works best. Memorizing different types of information may require different approaches.

- Reflect and digest. Take time to contemplate what you’ve learned. Ask yourself how the new information connects with what you already know and how you can integrate it into novel situations.

In conclusion, understanding how your brain handles information empowers you with valuable learning tools. By applying the principles of attention, encoding, storage, and retrieval, you can optimize your academic performance and extend this knowledge beyond the school. So, the next time you hit the books, harness the power of information processing theory to your advantage!

If you have friends, classmates, or colleagues who could find this article helpful, please share it with them!

Further reading:

- How to Study Fast in Less Time: 12 Effective Study Methods

- Transformative Learning Theory: Importance, Examples, and Benefits

- How to Improve Your Test-Taking Skills: Top Tips & Strategies

- Experiential Learning: Methods & Benefits

- How to Set & Meet Educational Goals – The Student’s Guide

- The Scaffolding Technique in Education: Benefits & Examples [Is It Really Useful?]

🔗 References

- 12 Learning Strategies to Help You Retain Information Fast: LifeHack

- Brain-based Techniques for Retention of Information: Loma Linda University

- What Students Can Do to Improve Information Processing: University of Washington

- Information Processing Theory: East Tennessee State University

- Information Processing Theory: Definition and Examples: ThoughtCo

- 50 years of research sparked by Atkinson and Shiffrin (1968): Springer

- Miller’s Law, Chunking, and the Capacity of Working Memory: Khan Academy

- Information Processing Theory and Approach: Thinkfic

- Learners as Information Processors: Educational Psychologist

- Learning Theories: Three Levels of Information Processing: TeachThought